RUTHLESSUNSCRUPULOUSPOWERFULFLAMBOYANTNOTORIOUS

IF YOU WERE IN HIS PRESENCE, YOU KNEW YOU WERE IN THE PRESENCE OF EVIL

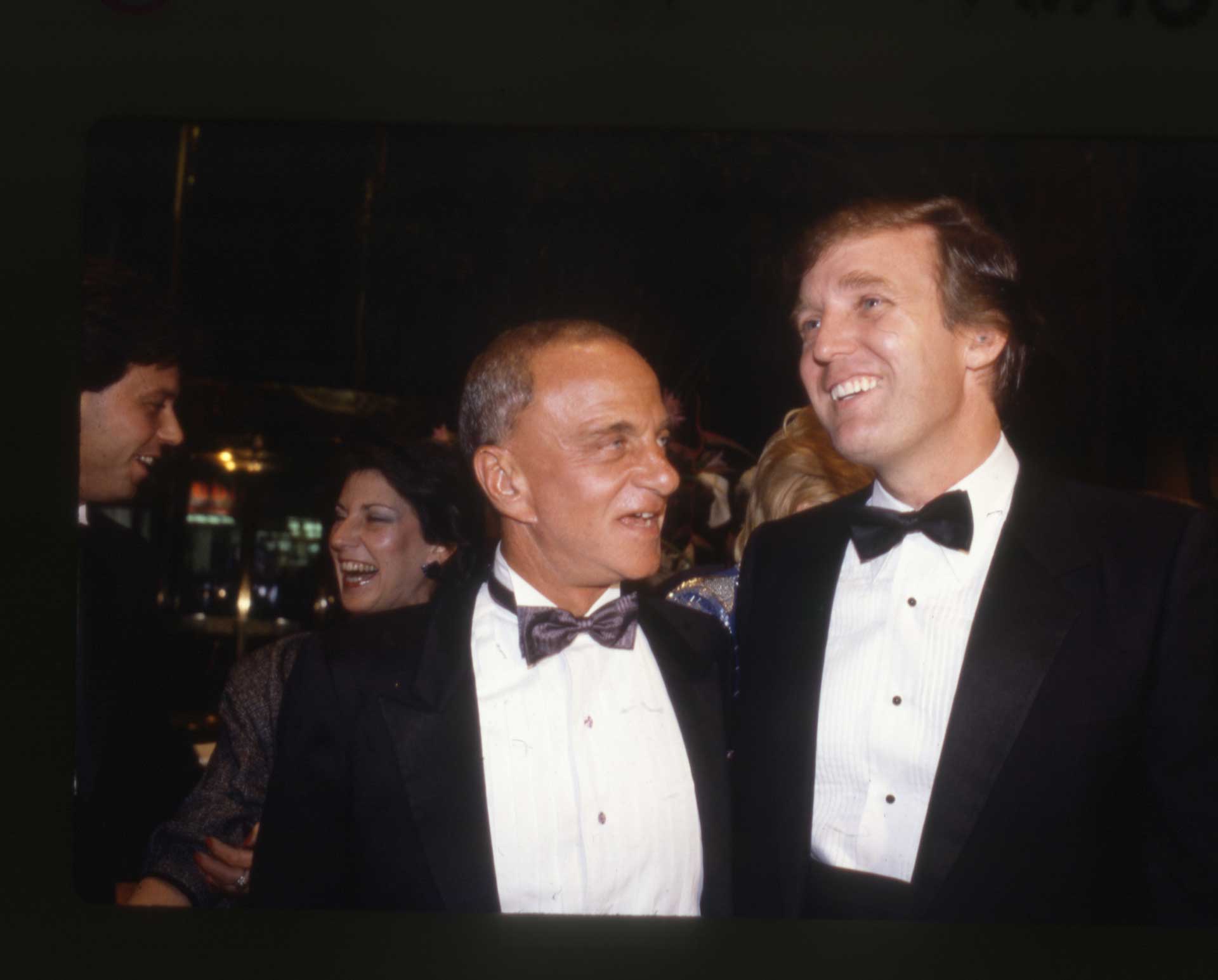

One of the most controversial and influential American men of the 20th Century, Roy Cohn was a ruthless and unscrupulous lawyer and political power broker whose 28-year career ranged from acting as chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Communist-hunting subcommittee to molding the career of a young Queens real estate developer named Donald Trump.

Cohn formulated his playbook in the 50s, but it is all too familiar today: always attack; never admit blame or apologize; use favors and fear to ensure support for your objectives; expertly manipulate the media to gain advantage and destroy your opponents; lie shamelessly, invalidating the idea of truth; weaponize lawsuits; evade taxes and bills; and, most importantly, inflame the prejudices of the crowd by scapegoating defenseless people.

Both, for those who remember Cohn and those who were too young to have any awareness of him, Matt Tyrnauer’s WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? lays out who Cohn was and how his lessons to his apprentice Donald Trump have shaped contemporary American politics.

WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? tells Cohn’s story from his birth in 1927 to his death in 1986, a picaresque journey that carries us from the Depression, through the Red Scare of the 50s, to the 70s and 80s New York high life of wealth, celebrity, and Studio 54. Known for Tony Kushner’s fictionalized version of him in his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Angels in America,” Roy Cohn’s best known exploits include: secretly and unethically communicating with the judge to send Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair; collaborating with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch hunt; spearheading J. Edgar Hoover and McCarthy’s crusade to hound homosexuals out of government; choreographing the New York State primary to split the vote and place Ronald Reagan in the oval office; spreading damaging stories about Geraldine Ferraro in 1984, scuttling her historic bid for the Vice Presidency; abusing the law to keep many of America’s murderous mafiosos out of jail; and looting the bank accounts of many of his legal clients.

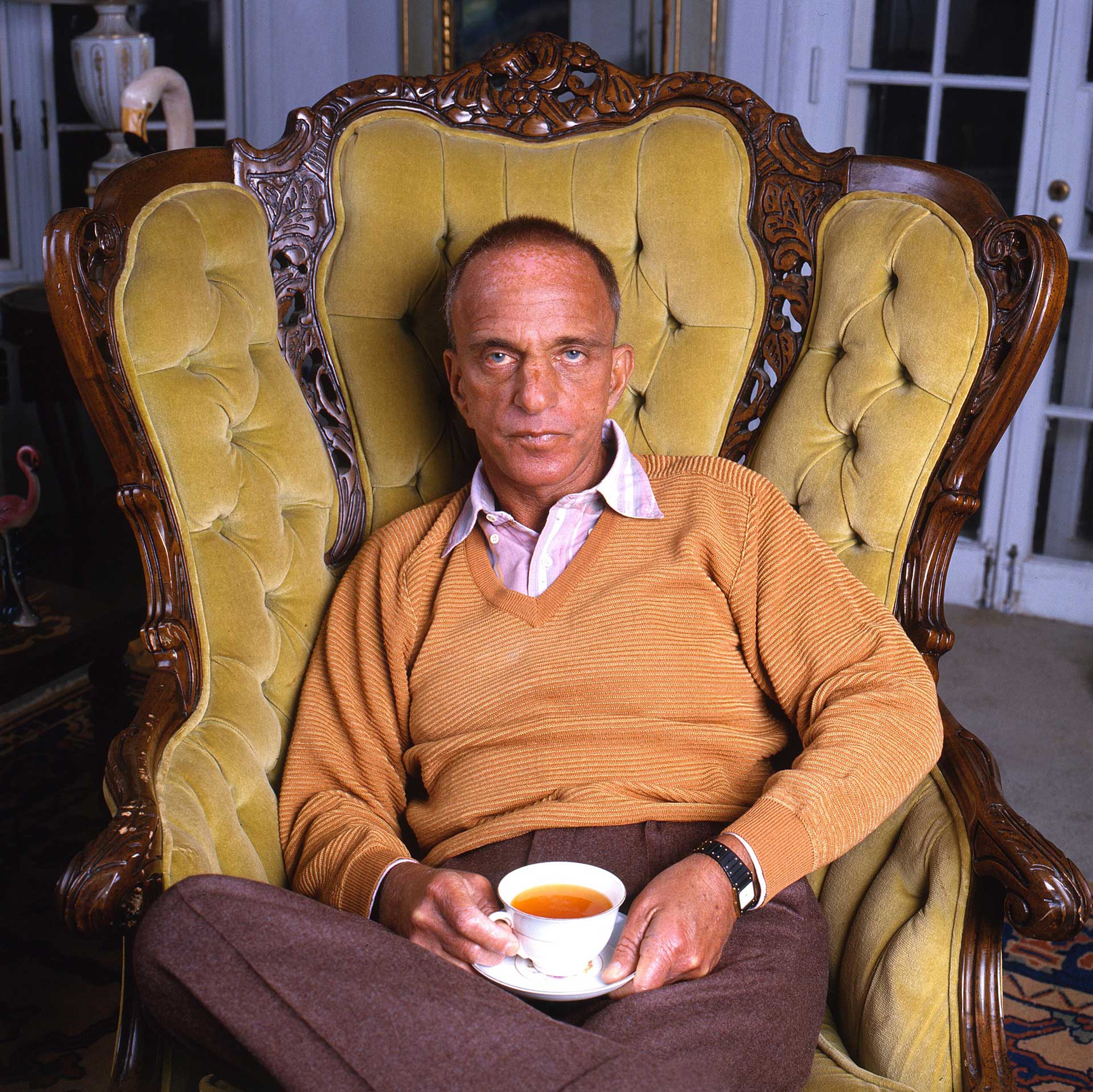

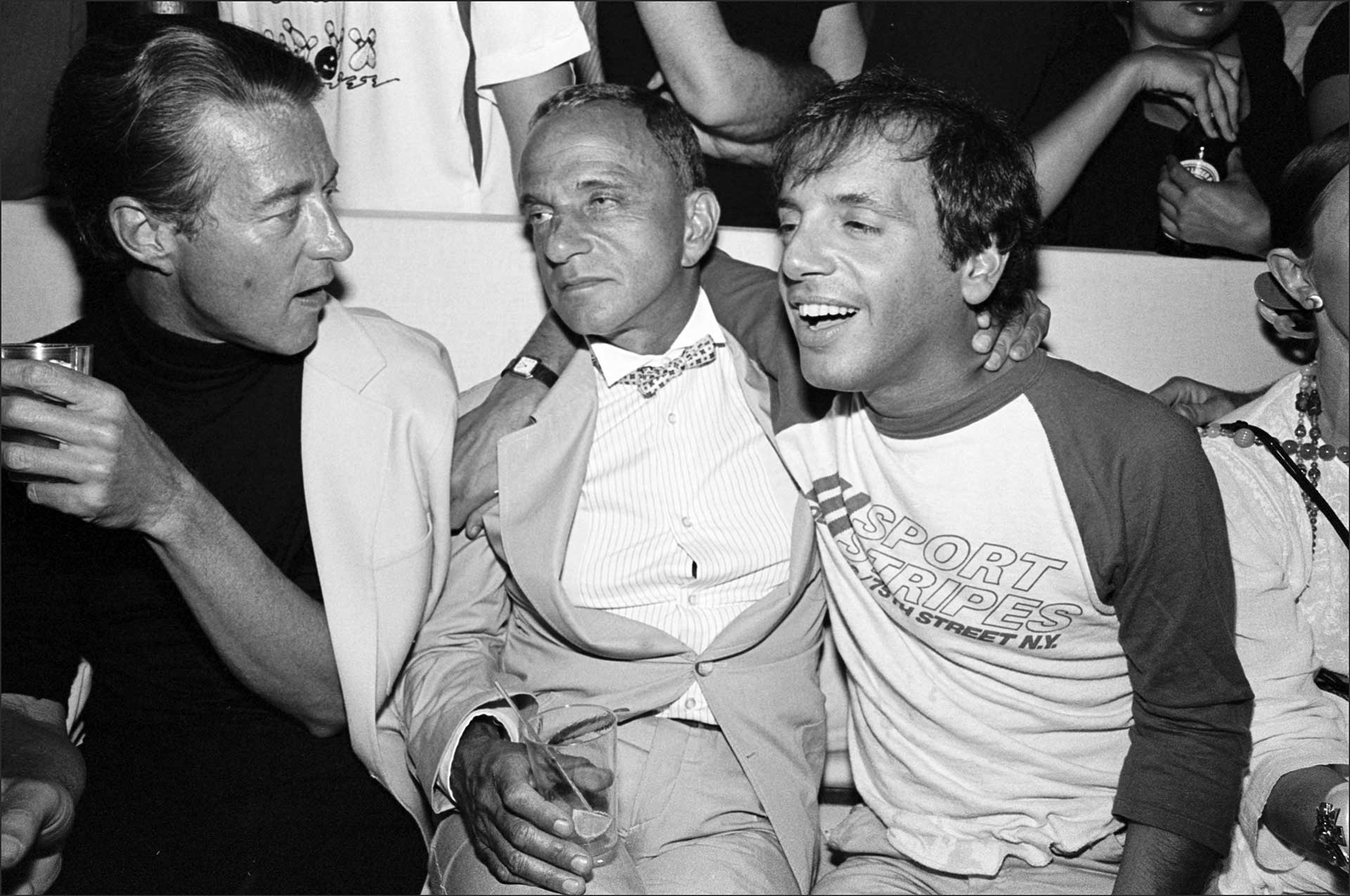

Cohn’s reputation as a flamboyant personality and courtroom pit bull drew the cream of Manhattan café society to him, from socialites and politicians to crime lords and a Catholic Cardinal. Despite his McCarthyite history and carnivore persona, members of the glitterati enjoyed his company. He had a large retinue of celebrity friends, including Andy Warhol, George Steinbrenner, and Aristotle Onassis. Cohn was a denizen of Studio 54, often accompanied by his male lovers, while adamantly denying his homosexuality to everyone. Cohn’s party finally came to an end when, disbarred and dying, his powerful friends, including his protégé Donald Trump, abandoned him. Cohn went out defiantly, refusing to admit he had AIDS, until the day he died of the disease.

Even those who think they know everything about Roy Cohn will find much that is new in this deeply researched film, which utilizes a great deal of material never publicly seen. Those with little previous knowledge of Cohn’s story will have their eyes opened to the sizeable impact he continues to have on us, despite being dead for decades. By showing how America’s current divisions are rooted in dark areas of our past, WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? offers an illuminating portrait of where we are today.

- Produced and Directed byMATT TYRNAUER

- Produced byCOREY REESER, p.g.a.

- Produced byMARIE BRENNER

- Produced byJOYCE DEEPANDREA LEWIS

- Edited byANDREA LEWIS

- Co-EditorTOM MARONEY

- Original Score byLORNE BALFE

- Music SupervisorLIZ GALLACHER

- Design and AnimationGRANT NELLESSON

- Executive Produced byDAVIS GUGGENHEIMJONATHAN SILBERBERGNICOLE STOTTSHANNON DILLJENIFER WESTPHALJOE PLUMMERLYN DAVIS LEARJOHN BOCCARDODEREK ESPLINERNEST H. POMERANTZLYNN PINCUSELLIOTT SERNELANDREA VAN BEUREN

- Co-Executive ProducersNION MCEVOYLESLIE BERRIMAN

- Co-ProducersBLAINE VESSANDREW TOBIASRANDY FERTEL, The Fertel FoundationJAMIE WOLFGRAHAM HIGHALISON SCHNAPPMICAH BASKIR

- Associate ProducerBRIDGET DEELY

About the Production

Director Matt Tyrnauer first became interested in Roy Cohn in 2016, while he was watching archival footage for his film STUDIO 54. As Cohn was the attorney for Studio 54 owners, he appeared often. “I’ve never seen anyone leap off the screen like Cohn,” says Tyrnauer. “I kept asking myself, ‘Why hasn’t there been a Roy Cohn documentary?’” After thinking it over, Tyrnauer realized that a Roy Cohn film would probably only be of wide interest if Trump won the Presidency. “When Trump won, Roy Cohn went from a footnote in history to become the modern Machiavelli who [helped] create a President of the United States,” says Tyrnauer.

Tyrnauer wrote the treatment for his Cohn documentary the next day. “I wanted to connect the dots for a general audience and show them who Cohn was and how he got us to where we are today,” says Tyrnauer. “While he might seem a relatively obscure figure in our political history, he has an outsized role in fashioning the predicament we’re in right now politically. As Gore Vidal said, ‘We live in the United States of Amnesia.’ I want this film to be an antidote to that.”

A few weeks later, I was in New York and ran into the writer and investigative journalist Marie Brenner, a long time friend and colleague, and asked her what she was working on. “I was astonished when she said, `I am writing about the relationship Roy Cohn had with Donald Trump.’ Marie had known and reported on them both in her early career and had a deep understanding of the larger and mostly unknown history of the world around them. I immediately said, `Let’s work on this together.’ We dove in and spent the next months pulling in many who had never spoken before, as well as Roger Stone, who Marie had been in contact with for her recent reporting. We were determined to illuminate the psychological back story of Roy Cohn and the forces that made him become a moral monster.”

The film takes us through the circumstances that forged Cohn’s singular persona, starting before he was even born, with the cynical transaction that made his parents’ marriage possible. As his mother Dora had a difficult personality and was generally thought of as unattractive, her wealthy parents were losing hope of her ever finding a husband, when she met Albert Cohn, a young Assistant District Attorney in the Bronx, whose ambition was to be a judge. At that time, the Democratic Party demanded sizable payments from the men they put on the ballot for judgeships, and Al lacked the funds. Dora’s parents were willing to provide the necessary cash if Al agreed to marry Dora. Shortly thereafter, wedding bells rang, inaugurating a lifelong loveless marriage. “Cohn is a product of the bizarre combination of his parents,” says Tyrnauer. “Dora was apparently very difficult and a dark soul, monstrously overbearing, while Al, who was a machine politician judge, introduced their son to the dark arts of the Bronx Democratic patronage machine.”

Dora was the consummate doting, hovering mother, who continued to play that role into Roy’s adulthood, living with him until her death, giving an oddly childlike dimension to aspects of his personality, which clashed with his bulldog reputation. To Dora, Roy could do no wrong. At the same time, probably due to her own issues, she imbued her son with a shame about his appearance. Obsessing about a little bump he had on his nose as a baby, she took him to a surgeon who botched the operation, leaving Roy with a lifelong scar to look at. Cohn’s father, by all reports kinder than his wife, introduced his son to the world of accumulating and maintaining power through doing favors and collecting on them—the so-called favor bank. “Roy’s father had Democratic, maybe even liberal leanings,” says Tyrnauer. “But that didn't mean that there wasn't a level of corruption and back-scratching and clubhouse politics behind all of that. And he passed an awareness of how that operated on to his son.” Young Roy quickly learned how to pull strings. By the time he was in high school, he already knew enough to be able to fix a parking ticket for one of his teachers.

In addition, Cohn’s personality was also twisted by his insecurity about being a closeted gay Jewish boy who could not be his true self. “I’m speculating, but I think he was aggrieved and traumatized by being considered short and ugly when he wanted to be tall and beautiful and admired,” says Tyrnauer. “Being the possessor of a brilliant mind wasn’t enough for him. He wanted it all, and he was told he could have it all by his mother. I think he was bitter, resentful, and scared.” Another source of bitterness for Roy was that his uncle Bernard Marcus, President of The Bank of The United States, was blamed for the collapse of banking during the Great Depression, and was sent to jail. This catastrophe caused considerable shame to Cohn’s elite family, and particularly to Dora, who felt that her brother Bernie’s fall was caused by a WASP conspiracy to make a Jewish banker the fall guy. The family’s well of indignation at Bernie’s persecutors rubbed off on young Roy, and he carried a chip on his shoulder for the rest of his life. “He always cast himself as a rebel and an outsider,” says Tyrnauer. “He did that even as he was accepting favors from the people who literally ran the government and were, by definition, the establishment.”

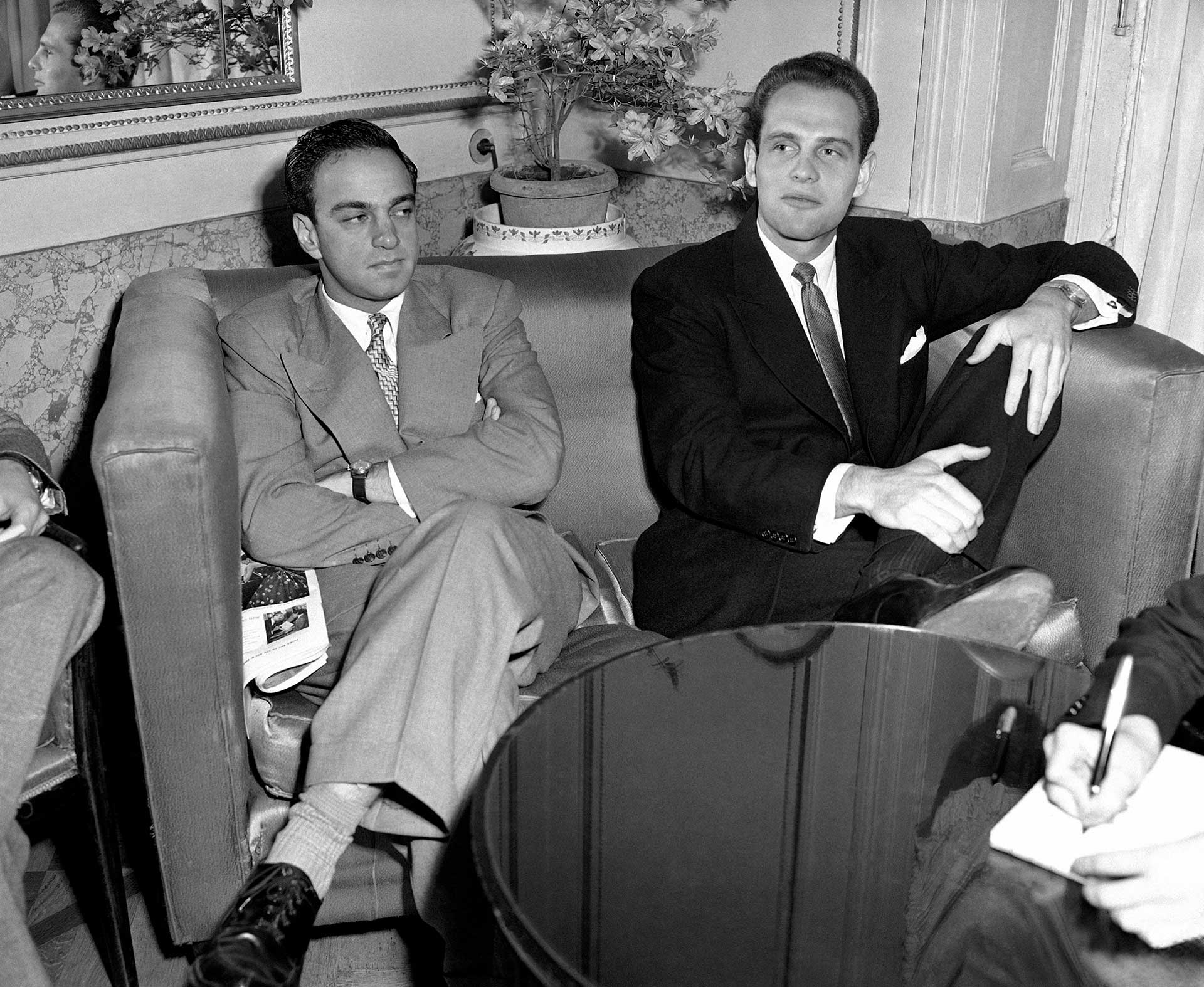

Cohn graduated from Columbia Law School at the unprecedented age of 20. He had to wait a year to be admitted to the New York bar, as the minimum age was 21. Two years later, he was serving in one of the most notorious jobs of his life, as one of the prosecutors in the trial of suspected communist spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Determined to send both of them to the electric chair, Cohn engaged in improper—and illegal—communications with Judge Irving Kaufman outside of the courtroom. While most historians who have studied the case believe Julius was guilty, it is unlikely that Ethel would have been found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt if not for Cohn’s interference with the judicial process and the fevered temper of the Red Scare era.

Roy’s education in the furtive workings of political gamesmanship, which began with his father, expanded as a result of his relationships with a series of powerful men. The first was gossip columnist Walter Winchell, who schooled Roy in the art of manipulating the media as a weapon to bend people to his will. Best known today as the inspiration for Burt Lancaster’s character J.J. Hunsecker in THE SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS, Winchell, in a time of more limited media, was an enormously influential, incendiary one-man media empire. “Winchell operated for a period as a kind of equivalent to the entire network of Fox News in that he was a right-wing, jingoistic, demagogic media megaphone,” says Tyrnauer. “Cohn helped him, like a hummingbird, pollinate the gossip trees of the country in that period.”

Cohn also had the extraordinary advantage in his media work due to friendships he had formed during his school days with such future media barons as S.I. Newhouse (Condé Nast magazines, Newhouse Newspapers, etc.) and Generoso Pope Jr. (The National Enquirer). Cohn met his second mentor, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, when he was working in the Justice Department in his early twenties. Utilizing the skills he had honed through his interactions with Winchell, Cohn made himself particularly useful to Hoover by spreading stories in the media about Hoover’s adversaries. Hoover and Cohn, both virulent anti-communists, also shared a methodology of amassing secret dossiers on their perceived enemies for the purpose of blackmail. “How ironic that two of the greatest persecutors of homosexual people in American history were closet homosexuals themselves, and how extraordinary that one mentored the other,” says Tyrnauer.

Cohn’s most infamous collaboration was with the communist-hunting Senator Joseph McCarthy, who sought Cohn out sight unseen based on his reputation. McCarthy wanted to know if it was hype or if Cohn really was as ruthless as everybody said he was. In joining McCarthy’s right wing drive to purge communists and gay people from the U.S. government, Cohn made a u-turn from his roots in the Democratic Party. Whether Cohn was a sincere red-baiter or whether he just wanted to separate himself from the anti-Semitic trope of the day that Communists were largely Jews, is unknown, but Cohn held firm to his anti-Communism to the end of his life. Cohn and McCarthy were so united in their obsessions and approach that it is hard to say who was the teacher and who was the student. McCarthy and Cohn’s chief tactic was “The Big Lie,” a propaganda technique devised and named by Adolf Hitler in his book Mein Kampf. The idea of The Big Lie is that while people might have the capacity to reject a small lie, they are incapable of imagining that anyone would have the audacity to invent a colossal one. Consequently, The Big Lie is more readably credible than a small one. If a Big Lie is repeated enough, it becomes truer than the truth. McCarthy would declare, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 State Department employees who are known members of the Communist Party,” when in fact he had no such thing. Though McCarthy changed the number of Communists in his lists, much of the public assumed it would be utter madness for McCarthy to make such claims if there weren’t any basis to them, and they believed him for a long time.

For Cohn, The Big Lie was advanced by the use of a number of highly aggressive strategies: always attack; never apologize; hit back a hundred times harder than they’re hitting you; turn your defeats into victories; and accuse your enemies of what you are guilty of yourself. Cohn’s ruthless, go-for-the-kill approach, something he had employed and enlarged upon as a prosecutor in the Rosenberg trial, expanded exponentially during his unholy alliance with McCarthy. The idea was not to root out facts. It was independent of truth and depended on the use of an inquisition to destroy lives and establish that Cohn and McCarthy were not figures to be trifled with. Cohn’s conviction that the source of all power emanates from inspiring fear coalesced during the Army-McCarthy hearings. The hearings were the result of the 26-year-old Cohn’s threat to destroy the Army if he was not able to secure special treatment for his recently drafted friend G. David Schine. While Cohn had spent much of his time with McCarthy hounding gay men out of government, it was clear to most observers—while perhaps not to Cohn himself— that Cohn’s over-the-top interest in Schine’s well-being was based on a passion more intense than collegial. “Before making this film, I didn’t fully comprehend what Army-McCarthy was,” says Tyrnauer. “I didn’t fully understand the homosexual subtext it had. It was really important for me to parse Army-McCarthy in the film, and to show Cohn at the center of it.”

While McCarthy was disgraced after Army-McCarthy, Cohn returned to New York and repositioned himself as a New York City power lawyer, with a clientele that ranged from jet set high society to the mob. Throughout the 60s and 70s, he became arguably the most powerful political fixer and behind-the-scenes player in New York life. During this time, he was indicted and acquitted three times for white-collar crimes. “I’m often asked, ‘How could Roy Cohn go from reviled assistant to McCarthy to darling of New York society in one week?’” says Tyrnauer. “My response to that is, ‘Have you met New York society?’ It’s a transactional system, and Cohn was the ultimate transactional human being. In New York, and one sees this to this day, people sidle up to questionable people, and the system promotes those who play the game. This explains how someone like this thrived for so many decades in plain sight.”

While his primary claims to fame rested in being vicious to all who opposed him, Cohn cultivated friendships with people like George Steinbrenner, Andy Warhol, Cardinal Spellman, William F. Buckley, Ronald Reagan, William Safire, Aristotle Onassis, Halston, Mayor Abe Beame, and mobster bosses Carmine Galante and the Gambino brothers. “Cohn occupied a unique position as the bridge between the legitimate world of politics and the illegitimate world of organized crime,” says Tyrnauer. “I don't think anyone has ever filled that dubious role as completely or as proficiently as he did.” Despite his fearsome reputation and McCarthyite baggage, people of all types and political persuasions liked him. “He could be fun, funny, charming, mischievous, naughty in a puckish way,” says Tyrnauer. “He did a lot of people a lot of favors, and as long as he wasn’t hurting them personally, they were more than happy to promote him.” Another reason high society sought his company is they knew they might need him someday to sort out their legal issues. “One of the blanket statements about him was that if you were on his good side, it was wonderful, but if you were on his bad side, it was terrible,” says Tyrnauer.

Cohn played a major behind-the-scenes role in many historic events, including the Rosenberg case, the McCarthy hearings, helping Ronald Reagan become President, clearing a legal path for Rupert Murdoch to form Fox News, and the promotion of the son of a Queens real estate developer in New York named Donald Trump.

David Cay Johnston says in the film: “Roy Cohn began this whole new mode of what you see today: get off the issue; attack law enforcement; attack the government; attack the press; and create phony issues so you can totally change the debate.” Cohn was always behind the scenes, the ever-willing fixer pulling the strings for young Trump, who grew to rely on him, particularly if there were any legal challenges. The film’s title reflects that: ‘Where’s my Roy Cohn?’ is not a question—it’s a complaint that Trump made in 2017 when he was upset that then Attorney General Jeff Sessions wasn’t behaving like his lawyer. “Trump missed the essential fact that the Attorney General doesn’t serve as the President’s personal lawyer, he serves the Constitution,” says Tyrnauer. “That's a direct result of his being the mentee of Roy Cohn, because that’s the way Roy Cohn behaved. Everything was for personal gain. The general welfare was never considered.”

Once Tyrnauer decided to make the film, he immersed himself in research. “I cast a wide net,” he says. “I got every book by and about Trump, Cohn, McCarthy, the Rosenbergs, and all the political and historical spheres surrounding Cohn’s life.” Tyrnauer watched hundreds of hours of archival footage. While he had research producers and archivists to help him, Tyrnauer tried to look at as much of the material as possible. “All of it leads to other tributaries of research, until a picture starts to emerge,” he says. As the research proceeded, Tyrnauer figured out what topics he wanted to cover, and assembled a wish list of people he wanted to interview. “It’s a careful process,” he says. “Going to the family was essential, because that’s the best way to figure out what makes Roy Cohn tick. Then you want a mix of reporters and eyewitnesses, but you don’t want too many reporters or authors. You want scholars who can add perspective. So it's all about the mix and it’s a bit about the casting, too.” As he did with all his previous films, Tyrnauer pre- interviewed everybody: “You definitely want people who are good at expressing themselves and good on camera.”

Tyrnauer felt that getting Cohn’s cousins involved was essential. Dave Marcus is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who wrote an article about Cohn for Vanity Fair. That piece was edited by Tyrnauer’s former editor, Wayne Lawson, who made the introduction to Dave, who then brought in Gary Marcus. WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? producer Marie Brenner, another of Tyrnauer’s colleagues from Vanity Fair, knew another cousin, feminist journalist and novelist Anne Roiphe. “There were no issues getting them to talk,” says Tyrnauer. “Gary Marcus liked Roy, and wasn’t aware of a lot about him. After he did his interview, he read up and asked to be interviewed again so he could specifically denounce Roy. That was fascinating.”

With his ruthless tactics, flamboyant personality, and cartoon gangster suits, Roger Stone is another well-known political operator who studied the Cohn playbook. “Stone knows what he’s doing and was brilliant on camera,” says Tyrnauer. “Cohn was very good on camera, too.” Part of the message of the film is that we live in a world of media celebrity and Cohn was a pioneer in making that. “I think Stone makes a kind of meta-contribution to that message, just by his sheer presence,” says Tyrnauer. Tyrnauer found one of Cohn’s boyfriends through two Studio 54 regulars, The DuPont Twins, who he encountered while making his film about the club. Tracking him down in California, the director began the long process of trying to get him to participate in the film. There were eyewitnesses who confirmed that he was Cohn’s boyfriend, and he knew things only someone who was very close to Cohn would have known. Still, he was ambivalent and reluctant to get involved. “He needed some convincing,” says Tyrnauer. “Eventually he agreed to do it, although he insisted on using a pseudonym.”

As Tyrnauer doesn’t use a narrator in his films and the subject of this one is no longer with us, the challenge was to bring Cohn to life and make the audience feel like they are seeing enough and learning enough from Cohn directly. His mission was to find the right combination of interviews with Cohn, TV profiles, talk show moments and critically, Ken Auletta’s 70s audio interview with Cohn, which had never been heard by the public before. Tyrnauer also got access to Roy’s personal photo archive from an anonymous source, which included everything from childhood photos to ones of Cohn with Donald Trump. There were also many pictures of Cohn with handsome, shirtless young men. “I juxtaposed a photo of Cohn with two or three guys who look like they're right out of MIDNIGHT COWBOY alongside Cohn’s speech to Auletta about how someone with a tough demeanor like him couldn’t possibly be considered a gay man.”

Tyrnauer teamed with editor Andrea Lewis for the third time on this film. Through their collaboration, the two have developed a language for combining archival material in a way that simulates the look of cinéma-vérité. An example of this is the footage of Cohn in his townhouse. “The footage was from a few sources, including b-roll from the “60 Minutes” profile that Morley Safer did,” says Tyrnauer. “We cut everything together in such a way to make it seem like you’re really inside that townhouse and getting a tour.”

WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? doesn’t follow a strict chronology, a technique Tyrnauer developed when he was a journalist. “When writing a story for Vanity Fair, I would purposely jump around on the timeline,” says Tyrnauer. “For example, I would start at the end and then flash back; if I started at the beginning, I would flash forward. It’s a technique I like and I think this approach makes a film more epic in scope and more cinematic. It presents more challenges and creates more work, but I think it results in a more sophisticated piece that is more of a trip than beginning at the beginning.”

While many people look at Cohn and see the epitome of evil, WHERE’S MY ROY COHN? encourages us to look beyond this kind of judgment to find the tangled human being he was. While the film doesn’t attempt to justify Cohn’s behavior, it does provide a series of clues to help us understand it: his mother’s smothering attentions; his insecurity about his looks and his height; his closet homosexuality; his shame about his Jewishness; and his indignation at the way the establishment mistreated his family. There is no doubt that Cohn’s tinderbox of fury and insecurity contributed to his raging need to control his world and administer pain on his adversaries. The irony of his life is that his key adversaries were representations of himself: Cohn was a homophobic, anti-Semitic member of the establishment. However, Cohn’s stew of contradictions and bitterness would not have mattered if he had not been as brilliant as he was and if he had not brushed shoulders with the kinds of unscrupulous people who could school him in the devious arts of power. Nobody will ever know, but without all these things coming together, Cohn might have been nothing more than another angry and broken young man, and he never would have cast the dark shadow on this country that he did.

As disturbing and as fascinating as the story of Roy Cohn’s life is, one undeniable fact is that, despite his certainty that he was untouchable, at the end he was brought down. The reason he was brought down is that some people refused to let his corruption go on any longer, and stood up to do something about it. Martin London, who was the Chairman of New York Bar Association’s Grievance Committee, dedicated to the discipline of malpracticing lawyers, relentlessly pursued Cohn until he was finally disbarred. At the same time, Cohn was weakened because, despite his fierce denials and claims that his disease was liver cancer, he was dying of AIDS. Many of his glamorous friends, including Trump, shunned him quickly. “In his own time, he was defeated,” says Tyrnauer. “It’s ironic that it came just weeks before his death. It makes him sort of an operatic figure. His life is laced with ironies and tragedies that are born and abetted from his hypocrisy and his horrendously bad character. In the end, it did catch up with him.”

Gallery